Strange Leaflet about Elixir - Page 3

- Author: Stephen Ball

- Published:

-

- Permalink: /blog/strange-leaflet-about-elixir-page3

How Elixir processes do

« back to page 2 || turn to page 4 »

If you like there’s a Livebook version of this post where you can actually run code and follow along. This was written to be a Livebook first, but works well enough as a post too.

I’ve been wondering, what are Elixir processes?

Elixir processes are microscopic lifeforms that reside within all living BEAMs.

Wait no sorry.

Anyway

Like your actual operating system running on your laptop an instance of the BEAM virtual machine is made up of processes. But these are BEAM processes which I will perhaps confusingly refer to as Elixir processes.

An Elixir process is the fundamental atomic unit of an Elixir application. If you’ve heard that Elixir has actor based concurrency: processes are the actors!

If you don’t know what actor based concurrency is well it’s the idea that you can effectively build concurrent systems in a reasonable way by assembling them out of actors that can send messages to each other. Actors have no shared state: only messages. In a very real way they are more like Alan Kay’s idea of objects than actual objects in object oriented programming because the objects in object oriented languages aren’t sending messages at all: they’re directly executing code by calling methods on their collaborators.

ANYWAY

So processes. They’re great, they’re self contained, they have an internal state, they can send messages, they can receive messages, they have a lifecycle, and their code execution is easy to understand because it’s internally iterative.

Elixir doesn’t build concurrency with complex channels of communication or delicate coordination of threads: it runs millions of processes that are individually simple to understand but powerful when organized.

ANYWAY?

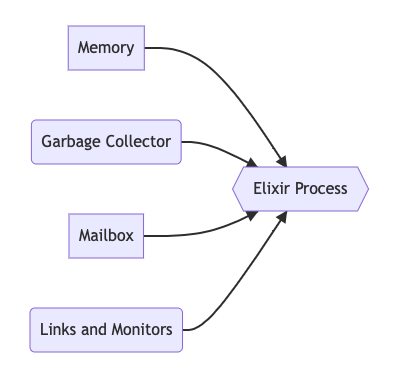

Let’s talk about the parts of a process.

And here let me give all the credit to Bryan Hunter’s amazing Waterpark: Distributed Actors vs the Pandemic

An Elixir process has

- Memory

- A garbage collector

- A mailbox

- Links and monitors

graph LR;

Process{{Elixir Process}}

Memory-->Process;

GC(Garbage Collector)-->Process;

Mailbox-->Process;

Links(Links and Monitors)-->Process;

Parts of the process

Memory

Each process has its own isolated and dedicated block of memory. Starting off at 2KB.

Garbage Collector

Each individual process, every single one. Has its very own isolated, dedicated garbage collector. This garbage collector has the easiest job of any language’s garbage collector. It doesn’t need to periodically stop all code execution and do a cleanup. It only has to watch over its own discrete unit of memory.

Mailbox

Each process has a mailbox. This is a huge deal. This is THE deal. This is what makes these processes actors. A process’s mailbox is the ONLY WAY it can talk to other processes or even to the operating system environment.

But do you need to learn a bunch of complex mailbox manipulation and terminology? No, not really. Processes reading from their mailbox is such a fundamental concept of work in the BEAM that generally you’re working at a higher level of abstraction. For instance you’ll implement callback functions that will be called when your process has work to do.

Links and Monitors

A link is a fundamental connection of two processes such that when either one dies then the other dies also.

A monitor is you, as a process, telling the BEAM that you want to be notified if a specific other process elsewhere in the system dies or crashes. If that happens the the BEAM will send you a message (again, to your mailbox) with the details.

The process scheduler

Again, one scheduler per thread per CPU core. The BEAM scheduler gives every process in the queue 2000 operations. After 2000 operations the next process gets 2000 operations and so on.

Let’s look at a process

The Elixir function Process.info/1 allows, well, seeing information about a process by its PID.

# this is our own pid for the current process

self()# this is our own process info

Process.info(self())self()

|> Process.info()

|> Keyword.keys()

|> Enum.map(&Atom.to_string/1)

|> Enum.map(&"* #{&1}")

|> Enum.sort()

|> Enum.join("\n")

|> IO.puts()

The above code shows us all the keys available in the data given to us by Process.info/1

Some of those available pieces of info may be less opaque now. We can see links, garbage_collection, reductions (operations), and message_queue_len (count of mailbox messages)

self()

|> Process.info()

|> Keyword.get(:links)

|> Enum.map(&Process.info/1)

|> Enum.map(&Keyword.get(&1, :dictionary))self()

|> Process.info()

|> Keyword.get(:garbage_collection)self()

|> Process.info()

|> Keyword.get(:reductions)self()

|> Process.info()

|> Keyword.get(:message_queue_len)We can see our process has some links, has some garbage collection stats, has probably run hundreds of thousands of operations, and has zero messages in its mailbox.

Let’s change that last one. Let’s send ourselves a message!

Sending our process a message

Process.send(self(), "hello me", [])Sorry, did you expect that to be an arcane and magical process? It’s literally a fundamental building block of the BEAM why would it be complicated?

self()

|> Process.info()

|> Keyword.get(:message_queue_len)

Oh hooray we have a message! Or even more than one if you clicked a few times on that Process.send/3 code block.

What could it be? How can we get it!?

Well, for one, our Process.info/1 has a :messages field now and we can query it.

Process.info(self(), :messages)But that isn’t actually receiving the message. To receive the message we have to receive it.

receive do

message -> IO.puts("I got a message!!! Amazing!!!! Contents: #{message}")

after

0 ->

IO.puts("No messages in the mailbox")

endYou can evaluate that receive block of code a few times (one for as many messages as you sent above) until you get “No messages in the mailbox”

That after block of code ensures that our receive block doesn’t do its default behavior of waiting for a new message if there is no message to receive yet.

And there we have it. A quick introduction into WHAT IS EVEN AN ELIXIR PROCESS?

« back to page 2 || turn to page 4 »